This article has printed in “Tejarat_e_Farda” magazine, Dated: Saturday, August 17, 2024.

https://www.tejaratefarda.com/fa/tiny/news-47498

Why Have We Fallen Behind in Developing Sports Infrastructure?

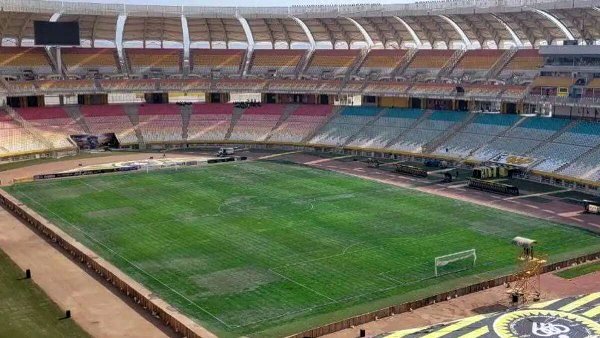

Worn-Out Pitches

Vahid Namazi, Journalist and Football Researcher

The poor quality of the Naghsh-e Jahan Stadium’s pitch has been a thorn in our side for days, becoming fodder for mockery by Arabic-speaking bloggers: “A return to the Stone Age” and “Severe injury warnings for players” are just some of the jabs highlighting the grossly negligent management and maintenance of a football pitch. Sepahan, one of Iran’s most ambitious clubs (alongside Persepolis and Esteghlal), not only lost its chance to reach the AFC Champions League Elite to UAE’s Shabab Al-Ahli but also drew widespread criticism for its deplorable pitch. Eighty-five years ago, when Amjadieh Stadium was built in Tehran, none of the Arab countries had football stadiums or had even taken steps to build them. Even Turkey only had Şükrü Saracoğlu Stadium, constructed 30 years before Amjadieh, which was a key reason for Iran’s rulers at the time to build a stadium in the heart of the capital. But the leaders of those same countries, now mocking the abysmal quality of our pitches, had dreams, plans, and determination. The result? Standard (even if small) and modern stadiums, proper infrastructure, and hosting major football tournaments in small neighboring countries.

While Barcelona’s iconic sports symbol is being demolished and rebuilt in under two years with a $1.7 billion budget, or right next door, Saudi Arabia constructs a modern 30,000-seat stadium for Al-Hilal in just six months, hosting over 10 major sports and cultural events and channeling profits to the club, Iran’s largest stadium—built over half a century ago with a roughly £400 million budget to be the pride of the nation’s sports—has become a festering wound on Tehran’s body. Its caretaker lacks the capacity to even renovate it, with repairs taking longer than its original construction! As a result, Iran’s national team, Esteghlal, and Persepolis are barred from using it, forced to wander the country, begging for a venue to host World Cup qualifiers and domestic league matches for a few weeks!

Iran’s football infrastructure is severely dilapidated, with no new investments made. The useless stadiums built by the ninth and tenth governments, located outside cities, lie abandoned and obsolete, proving how populism and sloganeering devastate a country’s capital resources. New investment projects across all sectors have stalled, the “capital stock” (the total measurable physical capital assets used in production) has flatlined, and the government’s infrastructure budget is gradually being phased out. Why? A significant portion of the country’s resources is spent covering pension fund deficits, banking system issues, and government budget shortfalls to heal deeper wounds. More than external pressures or resource shortages, the nation’s shoulders buckle under the weight of inefficiency and a lack of wisdom, widening the gap with the world every day.

Why Are Our Neighbors Investing?

Oil, the largest revenue source for Persian Gulf countries, is perhaps their most troublesome asset. Over the past six decades, the accumulation of oil wealth has caused problems, from revolutions and wars to government changes and inflationary surges, impacting their societies. Amid this, governments adopting a more moderate and forward-thinking approach have shielded their societies from these waves or minimized their impact. Balanced distribution of revenues across sectors and creating infrastructure capital have been key to escaping the inflation trap and pursuing development for future generations. Middle Eastern governments, long known for their oil dependency, have used these investments to signal their desire for greater global engagement (beyond their traditional oil-centric role) and demonstrate their commitment to becoming global players across various sectors. The looming end of oil revenues, driven by the world’s shift from dirty energy, has accelerated their sports investments, with a focus on maximizing current benefits and, crucially, nurturing capable future generations.

Investments by the UAE, Qatar (whose $220 billion World Cup and modern stadiums, alongside core infrastructure development, set this small gas-rich nation apart from its neighbors), and Saudi Arabia are typically state-driven (or public) and channeled through funding for educational centers, clubs, or teams tied to the private sector (derived from the state). For instance, Saudi Arabia’s Mohammed bin Salman, through Vision 2030 (an economic and social reform plan opening Saudi Arabia to the world), allocated over $100 billion to the Public Investment Fund (PIF), tying all national development to this fund. Saudi Arabia aims to host dozens of global championship events by 2030, with part of Vision 2030 targeting the Saudi Pro League’s inclusion among the world’s top 10 football leagues—a goal impossible without modern infrastructure. Though Qatar and Saudi Arabia’s football, like Iran’s, is state-run, with clubs and federations appearing as private companies or independent entities, everyone knows that without government support and investment in infrastructure and club budgets, football in these countries wouldn’t function. However, the nature of government involvement and investment in Saudi and Qatari football starkly contrasts with Iran’s, resembling South Korea and Japan’s models. Building and transferring stadiums (with long-term loans) to clubs and injecting infrastructure budgets from national funds—public but state-supervised—are among their strategies. For example, Saudi Arabia will dedicate eight new or renovated stadiums for the 2027 AFC Asian Cup and, with modern, boldly designed stadiums, host the 2034 World Cup, boosting tourism and infrastructure while rebranding the nation. Saudi Sports Minister Prince Abdulaziz noted that the country’s unprecedented £5 billion sports investment over the past three years aims to inspire its young population, boost tourism exponentially, and foster “job creation” and “growth potential” for sports federations. Official statistics show sports have increased Saudi Arabia’s GDP by 1%, with hopes that sports will play a central role in diversifying its economy away from oil.

Even Iraq, still haunted by the aftermath of war, has accelerated industrial and sports infrastructure development by rejoining the global community, engaging with the world, and increasing oil export revenues, overtaking Iran in oil exports. Over the past decade, the Iraqi government has built the 32,000-seat Al-Madina Stadium in Baghdad (2021), the 65,000-seat Basra Stadium (2013), the 30,000-seat Karbala Stadium (2016), and the 30,000-seat Najaf Stadium (2018), paving the way for football development. In the Kurdistan Region, stadium construction or upgrades by the Kurdish government have undoubtedly aided football development, human resource growth, and national revenue.

Our Problem Won’t Be Solved!

Why have our neighbors succeeded while we haven’t? Our biggest issue is that, over the past half-century, sports have never held a prominent place in Iran’s development plans. Unlike the rest of the world, Iran doesn’t view sports as a key development factor. Nurturing talented human capital to build the nation has only been taken seriously in a few isolated, greenhouse-like programs, and infrastructure hasn’t kept pace with population growth. Despite injecting vast, often dirty money into sports (especially football), the government’s approach remains utilitarian and unprofessional. For entirely non-sporting reasons, sports are never allowed to operate independently, preventing revenue generation, internal development, and self-sustainability. In developed or developing countries, football operates without government interference, with clubs functioning as publicly traded entities or private companies accountable to commercial systems. In Iran, hardly a season passes without the “still-non-private” Reds and Blues lamenting missing funds, budget deficits, and massive losses, always turning to the government for support. Due to inefficient human resources, lack of planning, and the absence of time as a factor in programs, there’s practically no roadmap for revenue generation by club managers. Industrial teams tied to quasi-state entities spend lavishly, connected to their parent organizations’ endless revenue streams. Revenue creation in Iranian football is meaningless; this industry only knows how to devour public and private capital.

The Right Global Model: A Revenue Domino Effect

Professional sports give societies a sense of pride and social participation. Grasping this single sentence would take us far along the development path. Alas, our rulers see sports as important only at certain times, otherwise treating it as a nuisance to be “dealt with” to avoid trouble! But the world, including our neighbors, long ago realized that “societal development comes through human and infrastructure development,” and the future cannot be built through force. Even in the world’s freest economy, the U.S., major stadiums are built with public funding and subsidies (in various repayable forms). A recent example is the $1 billion U.S. Bank Stadium for the Minnesota Vikings rugby club, built in 2016, with $498 million paid by the state government—directly from taxpayers. From 1990 to 2010, U.S. taxpayers averaged $262 million annually for new stadiums, justified by their economic impact. Stadiums are enduring projects requiring years of labor. While construction jobs vanish post-build, a stadium’s operation generates direct and indirect matchday revenue, providing local communities with new income and jobs. For instance, when parking attendants, restaurant staff, and other stadium workers spend their earnings, money circulates back into the economy. Without burdening people or their incomes, there are many ways to recoup stadium construction costs, such as leasing stadium names to sponsors. Clubs like Barcelona (Spotify), Arsenal (Emirates), and Manchester City (Etihad) have leased their stadium names through lucrative deals, using the revenue. Economists call this array of revenues the “multiplier effect,” where one dollar spent (by consumers, businesses, or the government) generates more than one dollar in economic circulation. Thus, the economic impact of millions spending at a team’s home games in its own stadium reaches hundreds of millions. Additionally, all direct and indirect stadium revenue (like TV broadcasting and advertising) returns to the market, subject to taxes, offsetting some government subsidies.

Some argue governments should fund welfare or educational infrastructure with growth potential instead of stadiums. However, the world’s evolving view of sports and the commercialization of disciplines like football prove that a modern stadium (even in a small city, tailored to population and club standards) generates revenue not just from matchday income but through numerous other channels. Consequently, concerts by major global artists have become a staple of large stadiums in Europe, America, and Asia, with new technologies enabling industries to host events in stadiums, leveraging their grandeur and facilities. Notable examples include recent mega-concerts at Real Madrid’s Santiago Bernabéu and England’s Wembley Stadium, generating substantial revenue for their owners.

A new stadium also spurs development in surrounding areas, including restaurants, commercial and residential complexes, increased interest in the region, and rising property values. Thus, building a stadium can be seen as an economic-development initiative in neglected or underdeveloped areas. Look at the placement of Tottenham, Arsenal, Chelsea, and West Ham’s stadiums, which have created wealth and revenue across London, and compare that to the closure of Tehran’s historic 25,000-seat Amjadieh Stadium. Instead of merely hosting ceremonies for departed sports heroes, with proper funding and private sector involvement (ensuring parking and safety requirements), it could have linked generations of sports enthusiasts and kept football’s passion alive in the city’s heart.

Sources:

The Cost of Building a Soccer Stadium

https://www.building.co.uk/cost-model-stadium-construction/5068838.article

https://research.stlouisfed.org/publications/page1-econ/2017-05-01/the-economics-of-subsidizing-sports-stadiums/